As Texas’ 89th legislature prepares to kick off the legislative session this week, all eyes are on the most hotly contested issues. Texas’ legislative body is only in session for less than five months every two years, and this session, one of the highest priorities for Republicans in both chambers is the statewide adoption of a school voucher system. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who leads the Texas Senate, announced in a press release that the initiative is his number one priority.

What are school vouchers and what’s the controversy?

Vouchers generally allow parents to use taxpayer money otherwise paid toward public education to instead fund a portion of their children’s private education, independent tutoring or other educational investments.

Voucher advocates say implementation of a voucher program that prioritizes low income households provides traditionally disadvantaged students access to better educational opportunities that can serve their specific needs. However, opponents have criticized the voucher movement heavily for reallocating money away from public education and for favoring wealthy households that already have the income required to fund a private education.

“That voucher is not going to cover the entire cost of the private school tuition,” education professor David DeMatthews said. “What we’ve seen in other states that recently passed vouchers is immediately the private schools raise their tuition … about 80% of the voucher users in the state are simply the families that already had their kids in private school because everyone else can’t afford the tuition.”

Proponents of vouchers advocate for the choice they give parents between sending their child to private or charter schools as opposed to potentially underfunded public schools.

Laura Colangelo, executive director of the Texas Private Schools Association, which lobbies state legislators on behalf of over 900 private schools in the state, said an ideal voucher proposal would target roughly 40,000 Texas students that would benefit most from an alternative education option but can’t currently afford it. Of the more than 5.5 million students in Texas public schools, that’s about 0.007%.

“Most families are going to stay in public school,” Colangelo said. “They’re happy in their public school, and they’re doing well. We want that to happen. This is just for those families that need another option.”

While Colangelo said vouchers benefit everyone, not just those that pursue a private education, some experts like DeMatthews believe vouchers are largely motivated not by parents and families, but by outside funders.

“There’s not really a voucher movement,” DeMatthews said. “There’s not a large group of parents that are advocating for this. Vouchers are being pushed mostly by a group of right wing organizations or … different (Political Action Committees) flowing into Texas to push this policy. There’s no grassroots movement for it.”

Michelle Rinehart, superintendent of rural Alpine ISD in west Texas, highlighted three central concerns she has with a voucher plan in Texas.

First, Rinehart, who holds a doctorate in educational leadership from Harvard, believes a voucher plan that focuses on private schools would not include similar oversight requirements for private schools and public school districts.

She said a voucher plan would need to either increase required oversight for private schools to a level that matches those facing public school districts, or would need to include a reduction in the amount of costly oversight procedures public school districts must obey to a level symmetrical with procedures private schools face. Rinehart prefers the former option.

Second, Rinehart pointed to some voucher programs’ history of negative academic performance, drawing on New Orleans as an example. In other states that have implemented universal voucher programs, some districts have seen test scores not only become stagnant, but even decrease.

Finally, she emphasized the cost of a voucher program, reiterating the $14 billion gap in identified needs costs on top of the state funding that some districts aren’t receiving in full, according to Rinehart.

“It doesn’t align with Texas’s conservative values,” Rinehart said. “We are not a state that believes in no public transparency and no accountability with public funds, and I say that as the CEO of a school district that has a lot of public accountability and regulation requirements to make sure that we are held accountable, as we should be, with taxpayer dollars.”

What happened last session?

This session won’t be the first time the Texas legislature has seen voucher proposals in recent years. The outgoing 88th legislature endured four special sessions in addition to their regular 140 day legislative session, multiple of which were focused almost entirely on approving some form of school vouchers.

The sessions were initiated by Gov. Greg Abbott, a strong proponent of vouchers who has been supported by pro-voucher donors across the country, along with other far-right conservative legislators in the state house.

“There’s been a pretty significant shift in the way the Republican Party in Texas has focused on education issues,” DeMatthews said. “I think a lot of it really has to do with the amount of campaign contributions coming from far right, ideologically driven groups and individuals, both within the state and outside of the state.”

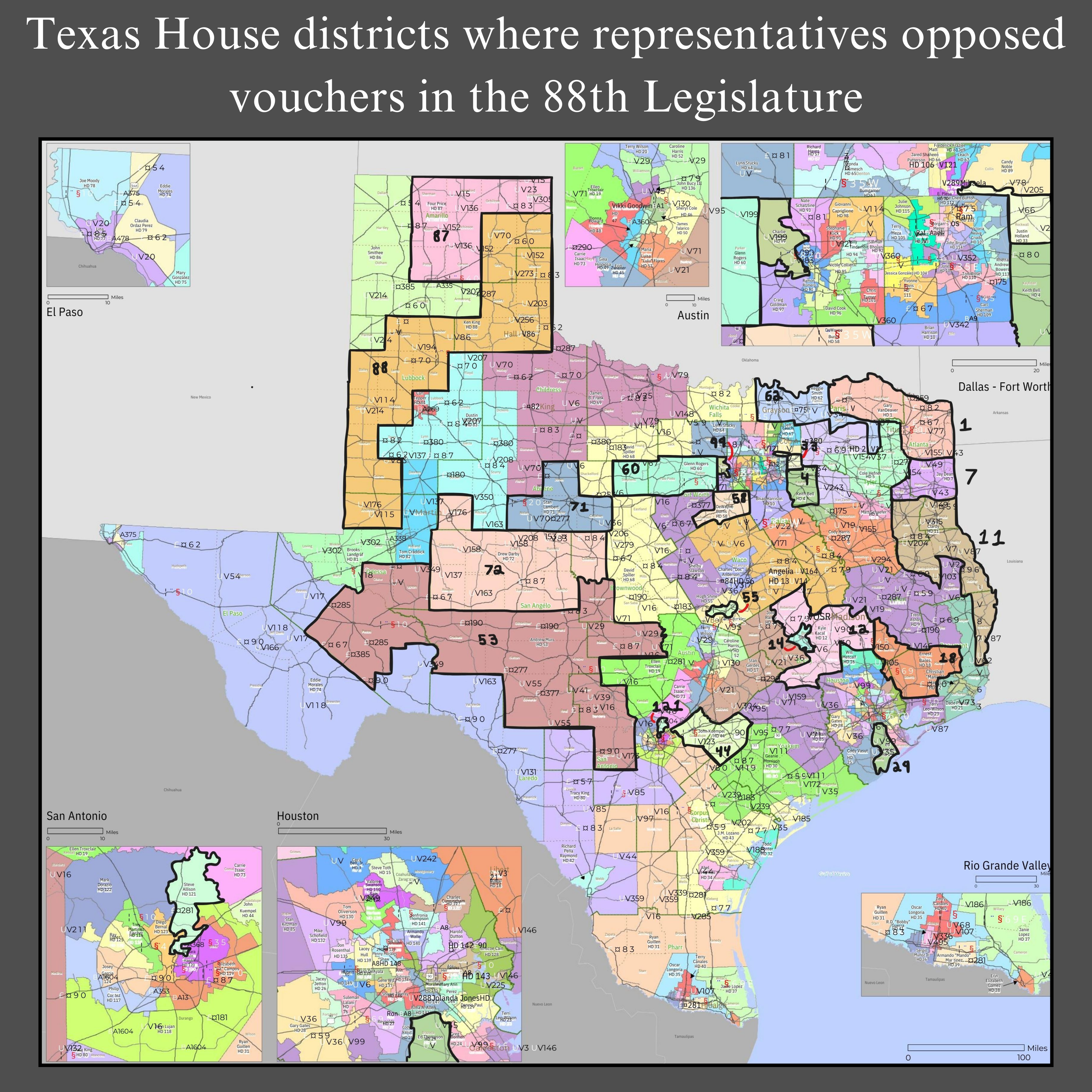

Despite Abbott’s insistence vouchers succeed, and his threats to fund opposition in primary races against legislators that vote against them, the push fell short last session. That failure was largely due to 21 Republicans in the Texas House breaking with their party and voting alongside Democrats to prevent the legislation from passing. Many of the representatives voiced concern over how vouchers would negatively affect their constituents in rural communities that wouldn’t have access to premier private or charter schools often found in urban areas.

“Texas has, over the years, fought the voucher movement because rural Texas leaders saw that there’s going to be a problem for them — you don’t get a good private school in Big Spring,” said Bryan Jones, government professor and J.J. Pickle Regents Chair in Congressional Studies. “Many of these rural areas organized to try to stop the movement because they knew that they were going to lose money. … It’s going to drain off the resources from the public schools.”

What happened to Republicans that opposed vouchers last session?

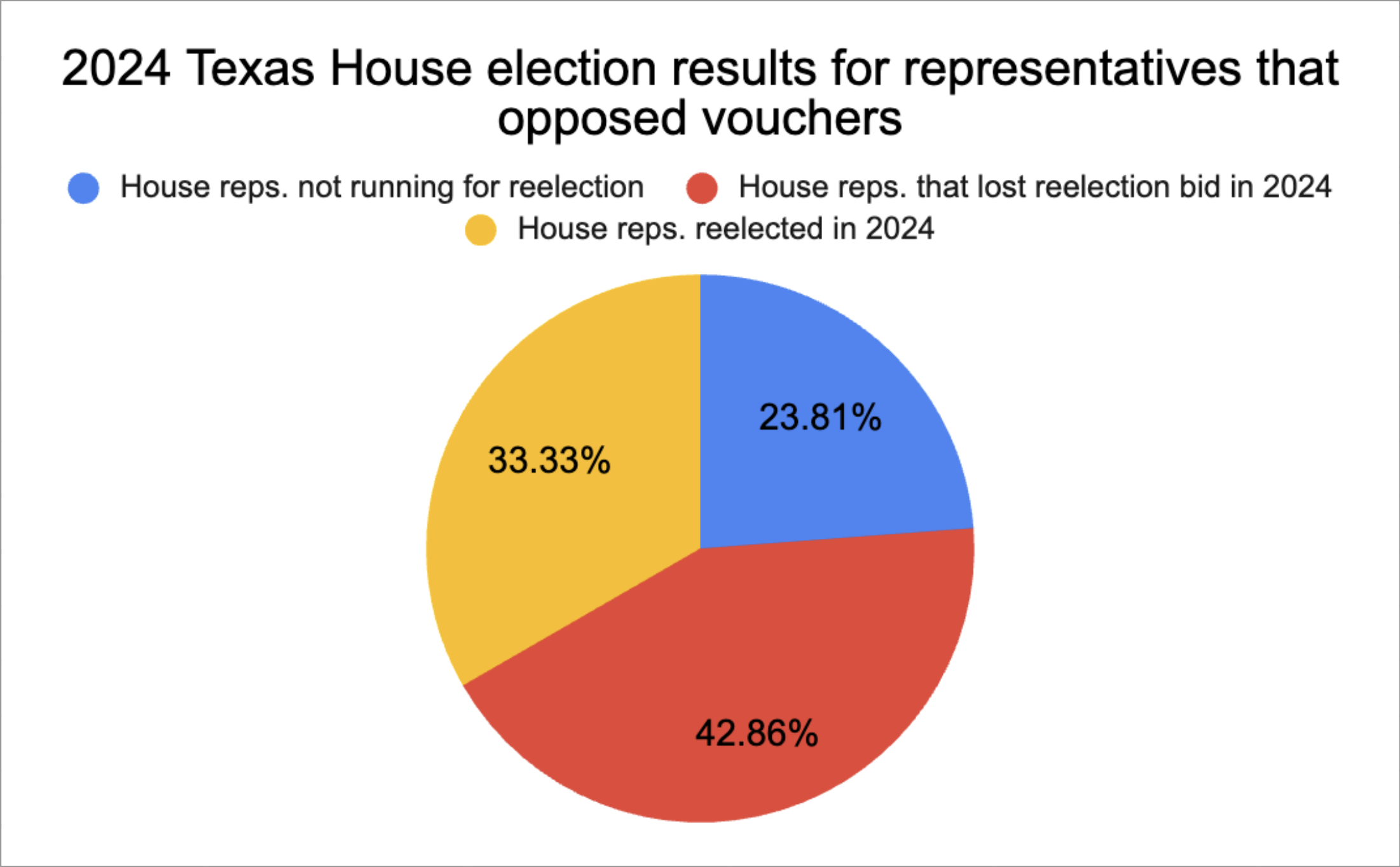

Abbott wasn’t lying when he swore to retaliate against insubordination — of the 21 Republicans that opposed vouchers in the House, only seven returned to their seats. Five chose not to run for reelection, and a whopping nine, more than a third, lost their bids for reelection. All nine faced primary race opponents funded by Abbott’s and Attorney General Ken Paxton’s supporters. It’s unclear whether the substantial drop was the result of opposition to school vouchers.

Source: The Texas Tribune, Ballotpedia and local county elections officesChart generated using Google SheetsJustin Doud/TSTV News

Source: The Texas Tribune, Ballotpedia and local county elections officesChart generated using Google SheetsJustin Doud/TSTV News

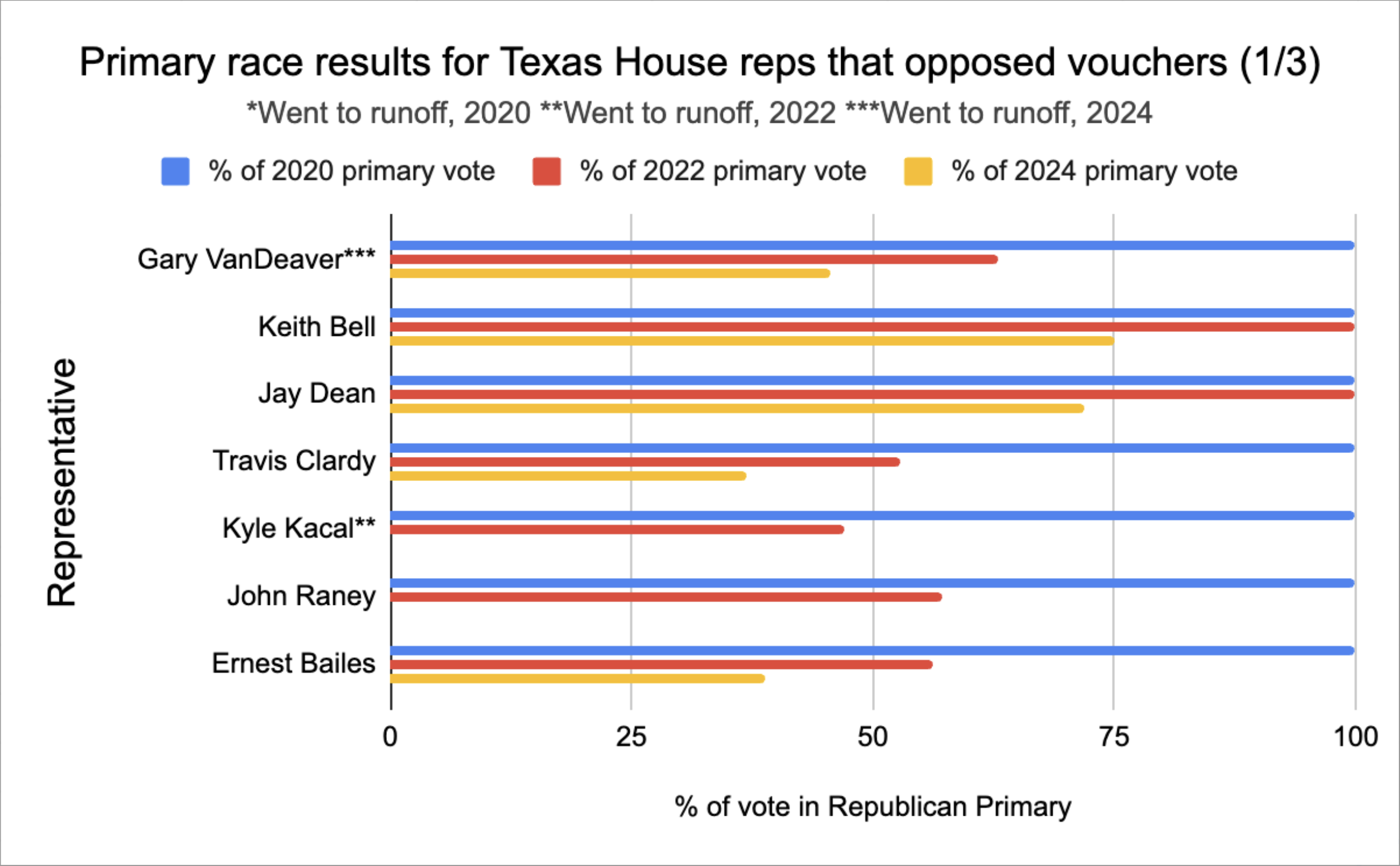

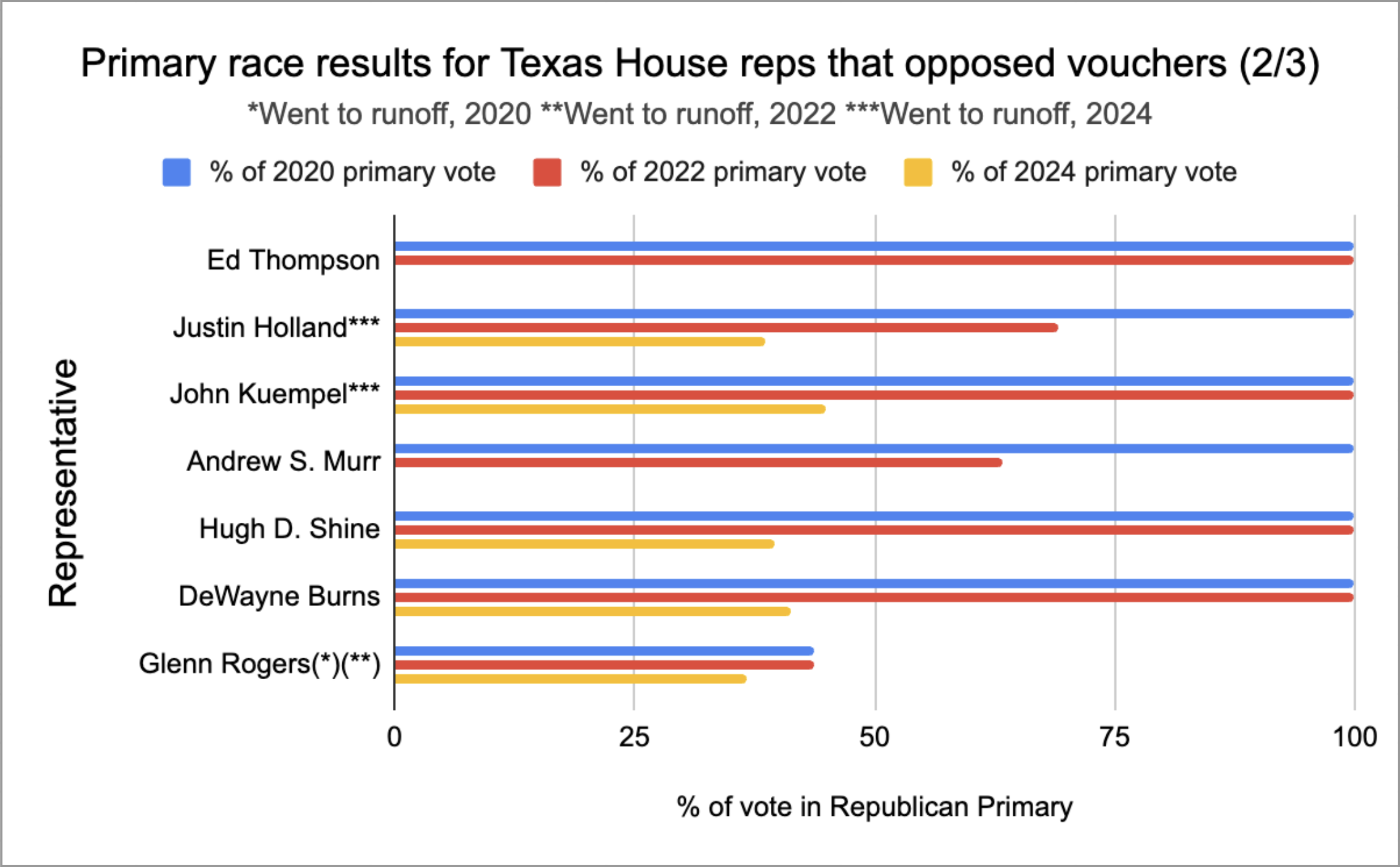

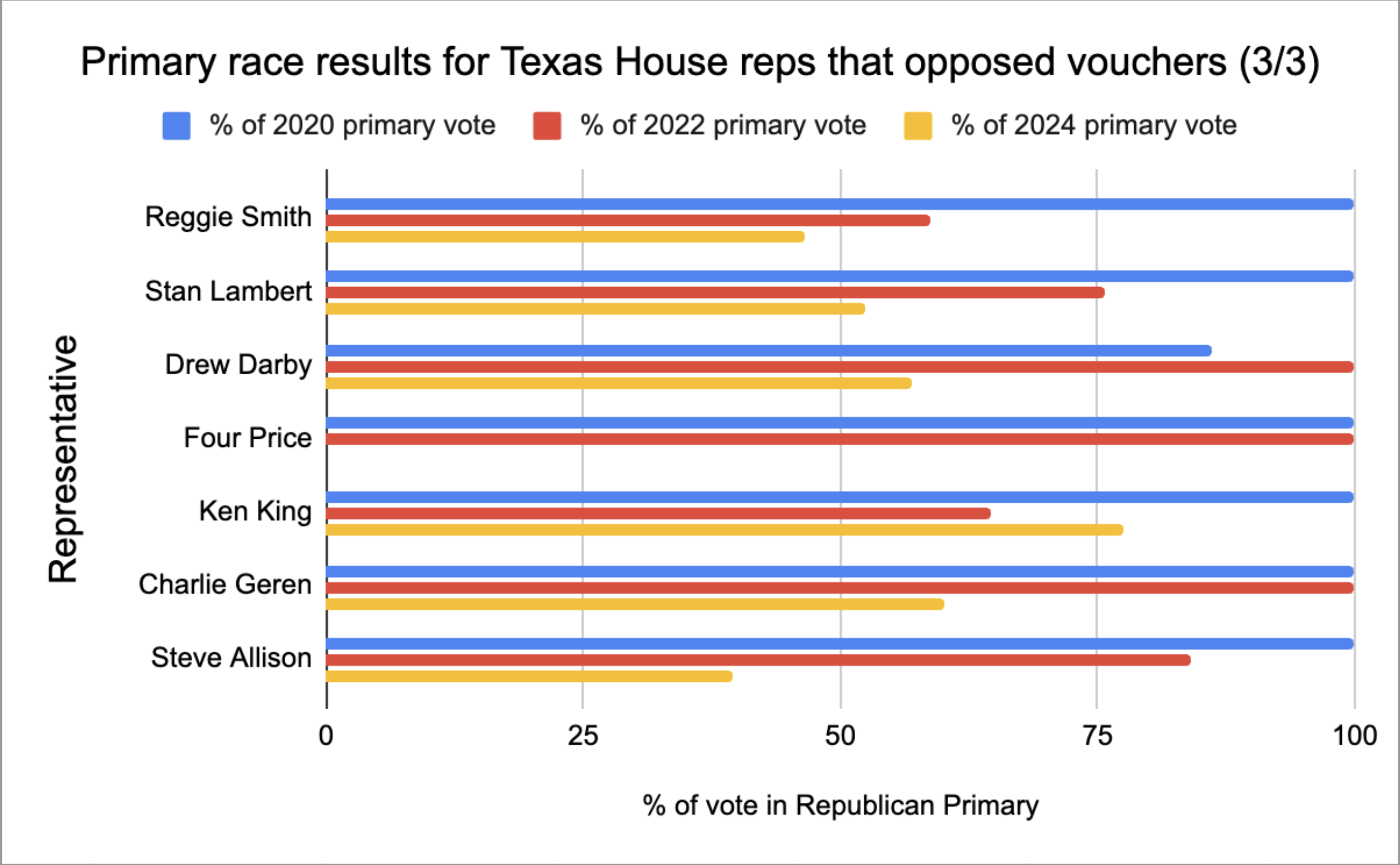

Only one of the 16 representatives that ran for reelection saw an increase in primary support from 2022 to 2024. The other 15 saw a decrease in primary support by at least 7%, and the average decrease was 31.87%.

Source: The Texas Tribune, Ballotpedia and local county elections officesChart generated using Google SheetsJustin Doud/TSTV News

Source: The Texas Tribune, Ballotpedia and local county elections officesChart generated using Google SheetsJustin Doud/TSTV News

In the three charts above, the blue line indicates a representative’s support in the 2020 primary election, the red line the 2022 primary election, and yellow lines the 2024 primary election, after controversial voucher debates. In the vast majority of representatives’ circumstances, 2024 saw a sharp decrease in support from their electorate.

Even when accounting for the single representative that saw an increase in support, Rep. Ken King (House District 88), the 16 representatives who ran for reelection still saw an average 29.08% decrease in primary support, with the lowest decrease coming for Rep. Glenn Rogers (HD-60) by 7.1%, and the largest drop in District 55, where Rep. Hugh D. Shine saw a 60.5% drop.

The Republican districts of the 21 representatives spanned across the state and were not isolated to any one geographic area.

Source: Texas House of Representatives, The Texas TribuneDistrict outlines and labels hand-drawn by Justin Doud in CanvaJustin Doud/TSTV News

Source: Texas House of Representatives, The Texas TribuneDistrict outlines and labels hand-drawn by Justin Doud in CanvaJustin Doud/TSTV News

Rep. Steve Allison (HD-121), representing a district just North of San Antonio, was one of the 21 members that faced retaliation after opposing vouchers. Allison was first elected to the House in 2018, and before that served on the Alamo Heights School Board. In 2020, he received 100% of his electorate’s support in the primary; after opposing vouchers, that dropped to 39.5% in 2024. As a result, he lost his bid for reelection in the primary to Marc LaHood, a pro-voucher challenger that went on to win the general election in November. Despite the loss, Allison is still outspoken about his opinion on vouchers.

“We’re in the bottom 10 in the country on school funding, and about the same position on teacher and professional compensation, and that’s where we need to be putting in the emphasis,” Allison said. “A voucher program is going to be very expensive, has constitutional problems that are impacting our public schools and are very troubling and we can’t lose sight of the importance of our public education system. We’ve got 5.5 million kids in our public schools that we’re really neglecting.”

Allison reiterated a number of concerns he had about the implementation of a voucher program, namely the shortcomings it could have in effectively serving underprivileged communities and the decrease in public school funding that would come as a result.

He pointed to misinformation around vouchers as a central problem, indicating a general misunderstanding about who a voucher program would benefit if enacted. He said he hopes that the new House Republicans will support their districts’ desires even if it upsets party leadership.

“It’s offensive to me that the governor takes the position of ‘I don’t care what your district or your constituents want, this is what I want, so vote this way,’” Allison said. “That’s just wrong. … I hope members will get a good backbone and recognize what their constituents truly want, and look at policy and not just politics.”

Allison had a very conservative voting record while in office, and said he voted with the governor on nearly every other issue.

What’s the impact?

The result of the severe shift is an increase in support for vouchers among elected members of the House in what was already a thinly held coalition against voucher success. Yet, as the start of the 89th legislature approaches, both voucher advocates and those opposed claim to have the votes for their stance to succeed.

Rep. Jon Rosenthal (HD-135), who represents part of Harris County, expressed confidence in vouchers’ potential for failure at a Harris County Democratic Party press conference Sunday, pointing to the bipartisan coalition that emerged in the 88th legislature.

“For everybody out there that thinks it’s an unavoidable eventuality, I have sat on the agriculture and livestock committee for two sessions and I have learned don’t count your chickens before they’ve hatched,”Rosenthal said. “We think the governor may not have the votes to pass this – it’s not a foregone conclusion … the first thing we’re going to do is try to defeat it outright, both through the numbers … but also procedurally.”

However, DeMatthews believe otherwise.

“The incoming legislature looks different,” DeMatthews said. “The governor and others targeted the rural Republicans who voted against vouchers. Many of them were unseated, and they have more radical right wing legislators in those positions that are very, very likely to vote for vouchers. And so it seems like, in the upcoming session, the governor and pro-voucher folks have the votes they need to get a voucher policy passed.”

Beyond the legislative arguments for or against vouchers, some educators like DeMatthews and Rinehart have pointed to the flaws vouchers have as an alleged improver of a students’ education.

“In the states that have implemented these large scale programs, researchers found statistically significant negative achievement impacts for voucher users,” DeMatthews said. “Those students do worse over multiple years academically. … It doesn’t work.”

Tensions are high around vouchers, with this session likely to draw vocal displays of support and opposition from the public and legislators alike. Abbott has attached vouchers to overarching school funding bills in the past in an effort to motivate legislators to pass the laws, drawing further criticism from education professionals, but Abbott said both will pass in 2025.

“Doctors have the Hippocratic Oath where you do no harm,” DeMatthews said. “Educators and policy makers should have the same oath that you’re not going to pass a policy that’s proven in multiple states over multiple years has negative achievement outcomes.”

Source: The Texas Tribune, Ballotpedia and local county elections officesChart generated using Google SheetsJustin Doud/TSTV News

Source: The Texas Tribune, Ballotpedia and local county elections officesChart generated using Google SheetsJustin Doud/TSTV News

TSTV News’ full interview with Rinehart is available now as a special episode of ‘On The Record’ on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.